Missing, Murdered, and Indigenous: Spreading Awareness and Speaking Up

by megan rowe

CW: Domestic violence, sexual violence, suicide

It’s been almost three years since Rosalie Fish ran in the Washington state 1B track and field championships for Muckleshoot Tribal School with a red hand painted across her face and the letters “MMIW” painted down her leg. Almost three years since she medaled in four events, each dedicated to a Missing or Murdered Indigenous Woman, inspired by Jordan Marie Brings Three White Horses Daniel, a Boston Marathon runner who had painted her face with the bright red handprint and dedicated each mile to a Missing or Murdered Indigenous Woman, inspiring Rosalie.

May 5 is the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People movement garnered national attention with the publication of the 2018 Urban Indian Health Institute report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The report included many sobering statistics, including that murder is the number three leading cause of death for Indigenous women.

The report also pointed out a crisis in reporting; of the 5,712 cases of missing and murdered women and girls in 2016, only 116 were logged into the Department of Justice’s database. According to the report, the city which reported the most missing and murdered women and girls was Seattle with forty-five cases. By state, Washington reported seventy-one cases, second only to New Mexico with seventy-eight.

But these statistics weren’t known to Rosalie when she first saw pictures of Jordan.

“I think the first thing I noticed was it’s another Indigenous woman, and she’s a runner, too,” Rosalie says.

Rosalie’s path to running wasn’t something she was ready to share when she first took the spotlight following that Cheney track meet, but is something she has become more comfortable sharing as she’s grown accustomed to her role as athlete activist.

“From being a high schooler and feeling hopeless, and then taking that feeling and taking action has taught me that anybody can do that,” Rosalie says. “Anybody can be that spark. Any youth really who’s experiencing that kind of adversity or is feeling hopeless about their situation, especially when it comes to social issues and social injustice. We all have the power to make great change, and that happens when we use our voice and we take that step into the unknown.”

Rosalie, a member of the Cowlitz Tribe, now runs for University of Washington and was recently named a 2022 Truman Scholar. But being a teenager was more than uncomfortable for Rosalie. She was attending a primarily white high school and simultaneously dealing with bigoted comments about the Indigenous and LGBTQIA2S+ communities as someone who was realizing she was attracted to women. All this, while being objectified.

“I was a young girl in an environment with older people, and I was realizing for the first time that to some of the students at my school, I was a sexual object,” Rosalie says. “I had no control over being catcalled, pinched, and feeling like my body was not my own.”

At home, domestic violence was a regular part of her environment, and Rosalie felt there was nowhere she could feel safe and secure. She began misusing her anti-depressants, and attempted suicide. Luckily, Rosalie survived, and in the aftermath, her tribe embraced her. She was released from the hospital just before her fifteenth birthday, but she still felt shaky. Then, she began to run.

“First of all, it creates like actual endorphins in your brain that make it really hard to be upset while you’re running, so [there’s] a biological component to it,” Rosalie says. “As I started to run more, I was outside, I felt a little bit less hopeless about everything. I could be away from the things at home and the violence at home at that time.

“It gave me something that I started to love about myself, being able to go out and run a mile, but then go out and run a mile and a half, and then actually run two miles. And I started to appreciate my body. And it’s one of the first times I actually began to love my body.”

She decided to transfer to Muckleshoot, and the tribal school’s coach recruited her for the track team. She felt useful for her team. And then, she saw Jordan in the Boston Marathon, and contacted her, asking permission to do the same at the Cheney meet.

Because Rosalie was running for her people, she felt a heaviness when running with the paint. Since that meet, she has run with paint a few other times. She says she still feels the heaviness, but now she knows to expect it.

Like Rosalie, Abby Yates encountered her first problems being female and Indigenous as a young girl. When Abby was a teenager, like so many teens, she was struggling to find acceptance. Abby is a Nooksack tribal member, but isn’t 100 percent Native American, so there were Native Americans who didn’t accept her as such, but she didn’t fit in with her non-Native peers, either.

Attending Mount Baker High School in Deming, Washington, Abby was passionate and outspoken about the things she cared about, mainly making sure everyone felt accepted. Though it wasn’t her intention, this ended up translating to popularity. She became the class president and was on the homecoming court. She also had a boyfriend.

“The more popular I became, the more boys that became interested in me, the worse the abuse got,” Abby says. “It culminated in him entrapping me under his bed.”

Her high school ex-boyfriend had a thick steel bed frame with coiled springs and a mattress on top. Abby wasn’t ready to have sex, and he wanted her to watch pornography with him and became enraged when she said she didn’t want to do that.

“I have no idea how long I was stuck under that bed,” Abby says. “I was teeny tiny, like 112 pounds at the time, but he wedged me to the point where I couldn’t move unless he allowed me to, and I just thought, ‘Okay, so my parents are going to have to find out that this is how I died.’ ”

While she was trapped, he forced her to watch the pornography. When he could see that she was crying and had closed her eyes, he told her to open her eyes, or he would shove her farther under the bed.

“I was already bleeding on my left side from the metal poking into my body, so I just sat there and tried to tune myself out to it,” Abby says. “I told him ‘I love you, I’ll do whatever you want, whatever.’ And he finally let me out, and I made a super loud noise, so his mom would come to the room, and that’s how I left.”

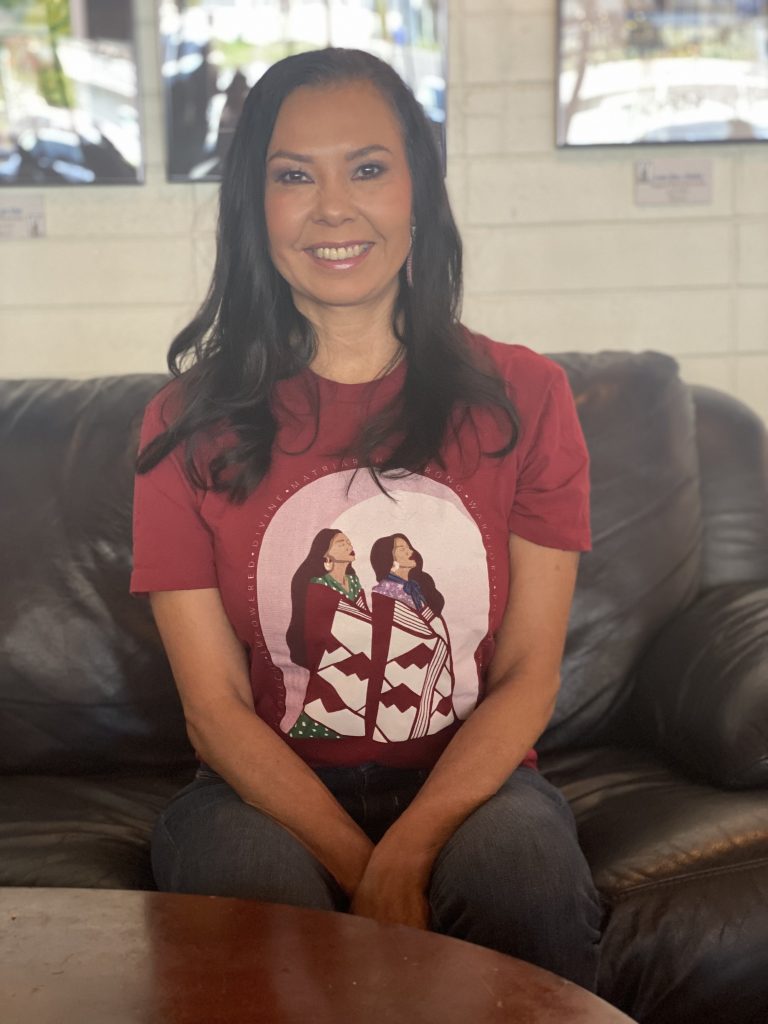

On May 4, Abby shared some of this story in a Facebook post, alongside a photo of her with a red handprint painted across her face. Professionally, Abby does marketing work for several tribes, and had spent the past weeks immersed in the movement readying for May 5, the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

“It’s been weeks of traumatizing research for me, and I just finally looked at my husband, and I said, ‘You know what, I have to tell more of my story,’ ” Abby says. “Because that could have been me. My twin sister could have been graduating high school without her twin sister. My family could have been celebrating every twin birthday with only one of the twins. It’s hard, but it needs to be told because I don’t think I was strong enough to endure it. I think my ancestors held on to me and pulled me out of that situation.”

While there are many issues compounding increased violence against Indigenous people, including jurisdictional issues and crimes not being taken seriously, Luhui Whitebear provided a concise summary of the systemic issues at play in a Portland Community College Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women/Relatives Keynote Event on May 3.

“The violence against Indigenous women, and Two-Spirit people in particular, began with contact. It’s well-documented why our bodies were attacked, not only because women weren’t viewed as human but also because our existence as political leaders and as negotiators and healers and all the roles that come with our identities that are, of course, contextual by the people — all of those structures were a threat to the colonizing mindset and structure where men, especially what we call … cisgender European men who were also Christian and had certain belief systems that were very patriarchal,” Luhui explains.

Luhui is an enrolled member of the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation, an associate professor at Oregon State University, and the center director of the Kaku-Ixt Mana Ina Haws, which provides a sense of home and community for Indigenous students at OSU.

” … When they’d arrived and saw Two-Spirit people and Indigenous women with that kind of power within their communities, it was a threat to what they wanted to bring here,” she says.

The 2018 report also led to legislation, on both federal and state levels. For example, Washington recently created a statewide alert for missing Indigenous people, Rosalie points out. A 2019 Washington bill also created two posts within Washington State Patrol–tribal liaisons for both Western and Eastern Washington.

Dawn Pullin has held many positions with her tribe—at one point, she was the Spokane Tribe CEO. But her current position is with the Washington State Patrol as the tribal liason for Eastern Washington. Dawn applied for the position after she saw a picture of Rosalie from that track meet.

“I started researching it, because I wasn’t even totally aware,” Dawn says. “When you’re from the community, you know the statistics already, so it wasn’t a surprise. But the activism on her part really brought it to the top of my mind.”

In her position, she is able to help be a go-between, helping someone through the process of reporting a missing person to the Washington State Patrol. Washington State Patrol also keeps a listing of missing Indigenous people in the state, which is updated about twice a month. As of May 2, there are 126 missing Indigenous people in Washington.

Dawn says she applied, because “I wanted to be part of an organization that was going to try to look for solutions.”

She and her Western Washington counterpart, Patti Gosch, teach classes to cadets. One of the exercises asks cadets to write down five things that are most important to them on a piece of paper.

“And then I go around, and I take two of those away,” Dawn says. “And they’re like, ‘Why are you taking that away? I’m not very happy about that.’ Eventually, we take it all away. And so we kind of equate that to like what happened to us historically: They took away our families, who could practice our language, our beliefs, and so we take all that away from them, and they’re kind of shocked and upset about it. So, that’s how we start off.”

While Dawn and Patti are working to reinstill trust between law enforcement and Indigenous people, Dawn says that’s “a heavy lift.”

“We’re talking about generations and hundreds of years of distrust, which is understandable,” Dawn says. “So the the House Bill, part of the verbiage is that our job is to build trust between the Washington State Patrol and tribal governments. And I just keep saying that’s a heavy lift, but it’s a start. Our positions are a start.”

For people who want to become involved in the movement, Rosalie advises that they reach out to their local group.

“Find an organization that’s doing the work and follow their calls to action,” Rosalie says. “Once you find an organization that is already there already putting out the calls to action, as allies, all you have to do is follow the calls to action that you can.”