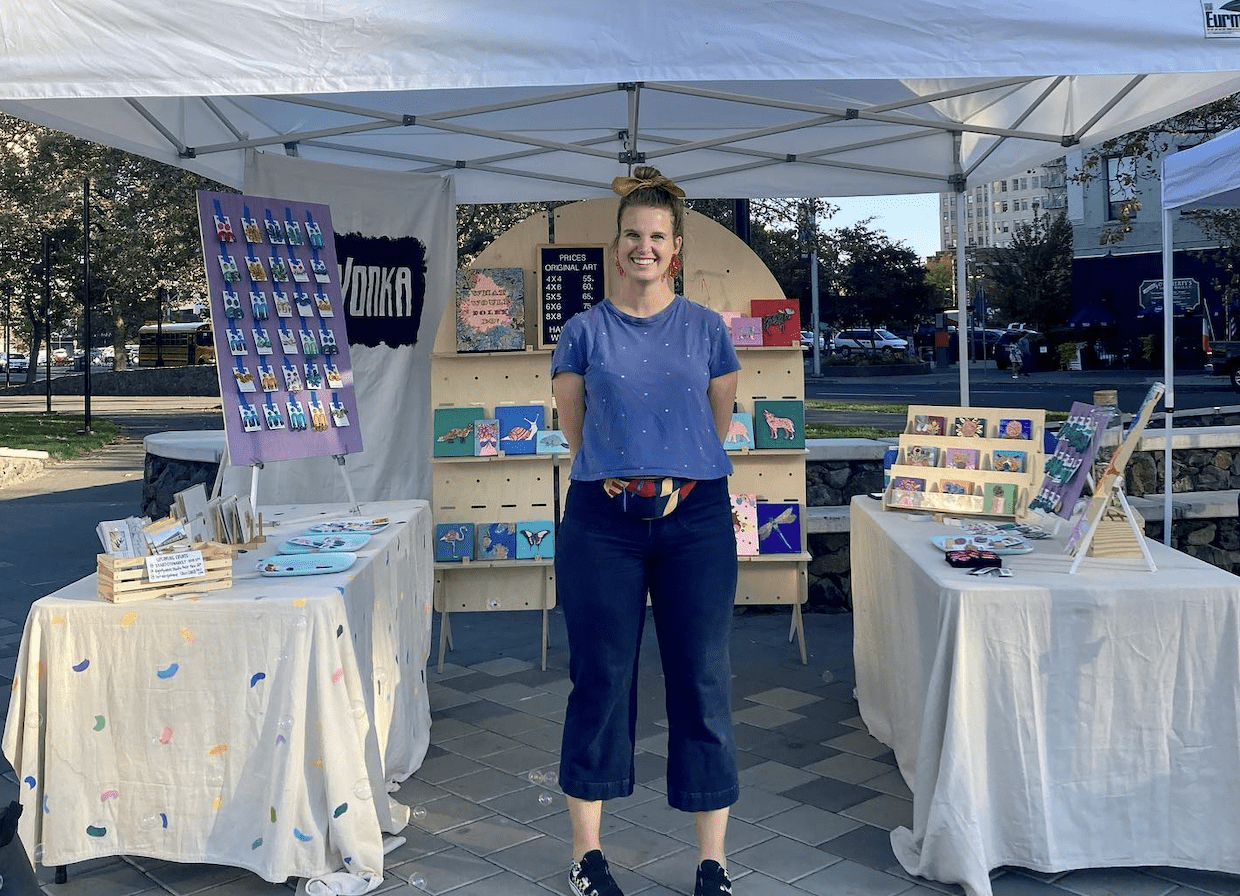

On Being Watched and Being Seen: How to Not Be Afraid of Everything

How To Not Be Afraid of Everything is an enticing promise—here, someone can share the secret of overcoming fear and anxiety, of living beyond the trauma that so many of us carry. How to Not Be Afraid of Everything, which is Jane Wong’s second full collection of poetry, delivers on this promise with poems that speak with a dazzling and honest voice about belonging, family, and trauma.

Wong opens her book with an epigraph from Lucille Clifton: “i will keep the door unlocked / until something human comes.” Clifton’s lines perfectly set up the emotional themes of the book: the speaker being made to feel by her neighbors as not-quite-human, an Other, and the longing and vulnerability she faces as she seeks connection in a country that sees her as an outsider.

Through these poems, the speaker explores what it means to be seen by other people, and how being seen is different from being watched or scrutinized. Being truly seen is an act of love, a recognition of the whole person with all their complexities and strengths. But many of us have experiences of being watched without being seen.

In the poem “Everything”, the speaker recounts her childhood experiences with feeling othered. Her teachers’ racist assumptions cause them to dismiss her and speak to her in a patronizing way. From her perspective, the speaker says, “I did not say a single word, not even when called on” because of the intense scrutiny of the teachers and administrators. They assume she can’t speak English, so she doesn’t. She is also the target of racist and misogynistic attention from a white man in the neighborhood, who makes a point to stare at her from his balcony and yell at her. She understands the power of staring something down: “I was ten when I willed a rock to fall off a ledge, just by staring at it long enough.” There is an implicit violence in this type of scrutiny.

Part of this scrutiny includes not seeing the speaker as a full person. In the poem “What I Tell Myself After Waking Up With Fists”, the speaker’s mother talks about her experiences, the apologies and emotional armor necessary for living in the United States as a Chinese woman. In one chilling line, she explains to her daughter this duality of being scrutinized and not seen at the same time, of being seen as less than an animal: “there, can you believe it, your mother says, a man—can cry over a dog’s dead body—but won’t look you in the eye.” The speaker herself often identifies with animals, either as a kind of defense or as an involuntary response to degrading treatment.

She is born in the year of the rat, and references to rats in these poems are a way for the speaker to explore the contradictions she faces as a Chinese-American. The rat is the first animal in the zodiac and denotes the fortunes of someone born in a Rat year, but the word “rat” has a definitively negative connotation in the United States. In the poem “I Put on My Fur Coat,” we read the perspective of the speaker’s mother, who feels she has to temper her desires in order to be a good mother and help her children adapt to this hostile landscape: “I stand in the center of every room / and ask: Am I the only animal here?” Ending the poem with that question – “Am I the only animal here?” – also creates a resounding sense of loneliness and isolation.

The book is divided into unnamed sections and begins with a single poem, “Mad” that takes the form of a Mad-Lib game, where important words have been replaced with blank spaces. This structure invites the reader to imagine which words are missing and is a way to show how others—white teachers and neighbors—filled in pieces of the speaker for her without her permission. Readers are able to deduce for themselves what kind of racist and misogynist language the speaker hears others use for herself. One of the blank spaces reads, “you have big eyes for a ____.” The casualness and commonplace nature of these racist and misogynistic comments underlines the cruelty and damage of them.

Even when talking about the messiness of trauma, Wong’s language is carefully chosen and structured. She expertly uses different forms in her book, including prose poems, couplets, tercets, and a sonnet crown in its own section. She also has three poems that share the title “The Frontier” and speak to one another. In these poems, the speaker communes with her family and ancestors. Her mother speaks in many of these poems, and Wong also works through the grief and longing for her family members who died during the Great Leap Forward, which was a devastating economic plan Mao Zedong enacted from 1958-1962. The Great Leap Forward was responsible for famine and the mass starvation and death of anywhere from fifteen to fifty-five million people.

The poems in this book speak about the importance of food and the theme of consumption, in general. The speaker talks about the abundance—to the point of obscenity—of food available in this country, and the luxury of letting bread go stale. Her experience growing up in this food culture contrasts with her mother, who grew up in a place where she could only afford to eat meat once a year. In “The Frontier,” the speaker reminisces about the recipes and foods that have become so comforting and nourishing for her family, and also the fear and anger that this country will try to assimilate and colonize that piece of them:

My grandmother salvages the sweet

peels, brown like the bark

of a tree I have loved for years. I worry

this recipe will be in Food & Wine.

European discoveries of “peasant” food.

My comfort: stir-fried tomato

and egg, appears in ____.

Do not look this up.

But the frontier beams and thickens

each glowing intestine, pink and

pinker still: Comfort for you, comfort for all!

Do not look this up.

In this poem, she recalls the Mad-Lib blank spaces used in the opening poem “Mad”. And the refrain of “Do not look this up” echoes the sentiment of that first poem—do not label me with your ideas of who you think I am.

“How To Not Be Afraid of Everything,” the titular poem, is a poem about survival—survival of the self that refuses to be homogenized and colonized, that refuses to be made small. The opening lines of this poem show the difficulty of standing up for oneself without apology: “How to not punch everyone in the face. / How to not protect everyone’s eyes / from my own punch.” She speaks openly about looking over her shoulder all the time, how fear has become part of her daily experience. The weight of this fear is something given to her by this country, not something she has chosen: “That a horse’s neck snaps from the weight / of what it carries, from the weight of what / we give it to carry.” But at the end of the poem, she chooses to go out into the world without fear. She refuses to take on others’ perception of her.

In “Cosmology,” the speaker rejects the notion that existence is about power. By drawing strength from her family and ancestors, she finds a way to live authentically and without fear:

I repeat: I will not be afraid

that the world is about power.

My ghosts fill me with feathers,

my lungs: a mane unplucked.

Danielle Weeks

Danielle Weeks is a poet living and working in Seattle. She earned her MFA from Eastern Washington University’s creative writing program. While there, she served as Poetry Editor for Willow Springs and also worked for the university press Willow Springs Editions. Her poetry has been published in The Gettysburg Review, Redivider, and Salt Hill Journal, among others.